- Blog

What is Affiliate Marketing Fraud

What is Affiliate Marketing Fraud

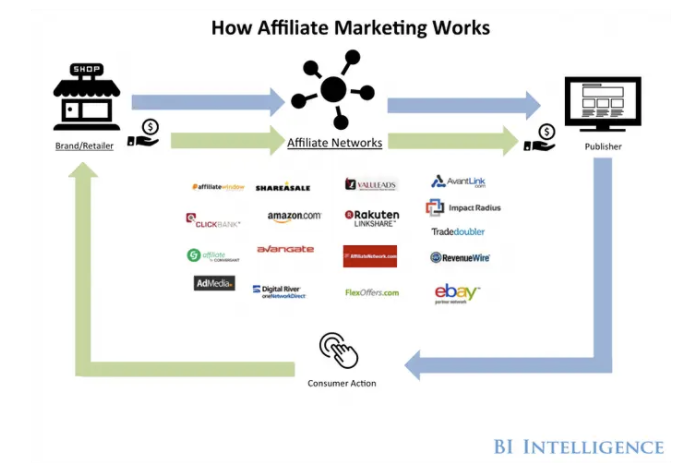

Affiliate marketing can be a very effective way to drive traffic to your website, increase sales and build your customer base. Affiliates can attract customers who might not have come across your website otherwise. It’s no surprise that 81% of advertisers and 84% of publishers use affiliate marketing as part of their broader marketing strategy.

Figures prove the effectiveness: in 2016, affiliate marketing accounted for 16% of US e-commerce orders, outperforming social commerce and display advertising.

Also, publishers depend on the income from their commissions: Approximately 15% of the digital media industry’s revenue comes from affiliate marketing.

However, even though affiliate marketing offers many opportunities for businesses, there are also risks to be aware of. Because where there is money to be made, the fraudsters are not far away.

In this article, we will take a closer look at affiliate marketing fraud. What it is, what the most common types of affiliate fraud are, and how you can spot indicators in your campaign data.

What is affiliate fraud?

“Affiliate fraud refers to any false or unscrupulous activity conducted to generate commissions from an affiliate marketing program. Affiliate fraud also encompasses any activities that are explicitly forbidden under the terms and conditions of an affiliate marketing program.” (Investopedia)

To put it simply: Affiliate fraud occurs when fraudsters fake conversions. This can be done using various methods, as there is no one type of affiliate fraud. In fact, there are several ways fraudsters can exploit affiliate marketing programs, whether they are based on CPM (cost-per-mille), CPC (cost-per-click), CPL (cost-per-lead), or CPA (cost-per-acquisition) payment models.

Most common types of affiliate marketing fraud

Similar to the various methods of ad fraud, fraudsters have developed various tactics to commit affiliate marketing fraud and exploit tracking and attribution to claim unjust commissions, damaging marketers and the bottom line of many businesses.

1. Cookie stuffing or cookie dropping

In the “cookie stuffing” (or “cookie dropping”) process, the user’s browser is “stuffed” with many different cookies belonging to different advertisers while visiting the affiliate’s website without their knowledge. If the visitor subsequently visits one of these advertisers’ websites and makes a purchase, the affiliate receives a commission without actually having been involved in leading the visitor to that website. The affiliate is being paid for an advertising service that he did not provide.

The most high-profile cookie-stuffing case dates back to 2014, when Shawn Hogan, the CEO of online marketing company Digital Point Solutions, was sentenced to five months in prison for defrauding eBay of an alleged $28 million in online marketing fees.

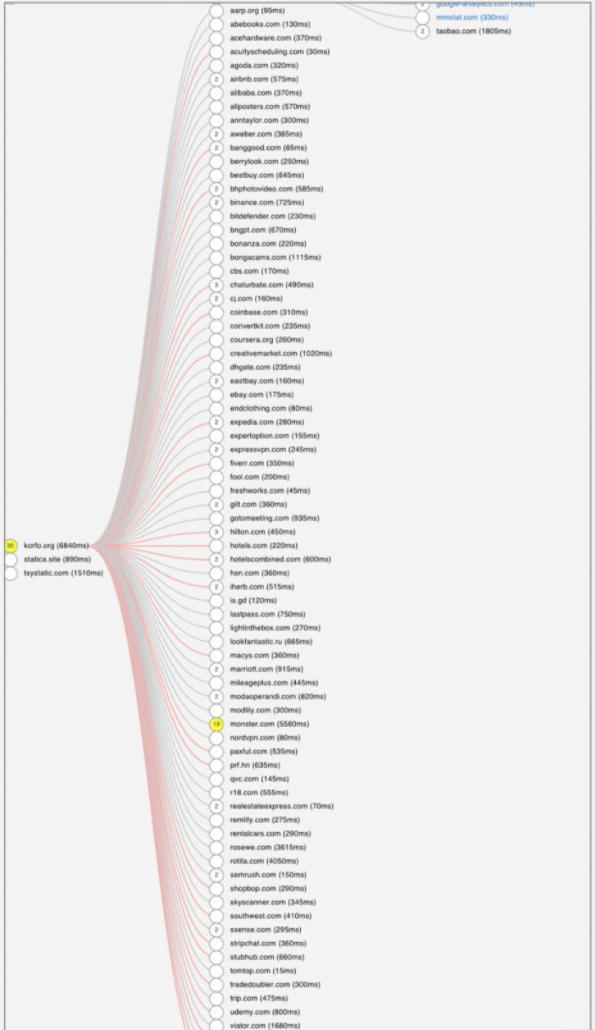

The following diagram shows an example of a single page loading almost a hundred other pages in hidden iFrames and popunders. On each of these pages the AffiliateID is included and the cookies are dropped without the user’s knowledge.

2. Browser toolbars and extensions

Similar to the cookie stuffing method mentioned above, developers of browser toolbars and extensions promise their users some benefits, such as shopping discounts, only to secretly place cookies in the user’s browser in the background. The only difference is that users do not need to visit a specific website to receive the fraudsters’ cookies, but use their browser toolbars and extensions.

A prominent case of cookie stuffing via browser extensions was carried out in 2019, when two fake adblocker extensions from Google’s Chrome Web Store with more than 1.6 million weekly active users dropped cookies for more than 300 popular websites, including Booking.com, Aliexpress, and Teamviewer.

See what’s hidden: from the quality of website traffic to the reality of ad placements. Insights drawn from billions of data points across our customer base in 2024.

2. Browser toolbars and extensions

Similar to the cookie stuffing method mentioned above, developers of browser toolbars and extensions promise their users some benefits, such as shopping discounts, only to secretly place cookies in the user’s browser in the background. The only difference is that users do not need to visit a specific website to receive the fraudsters’ cookies, but use their browser toolbars and extensions.

A prominent case of cookie stuffing via browser extensions was carried out in 2019, when two fake adblocker extensions from Google’s Chrome Web Store with more than 1.6 million weekly active users dropped cookies for more than 300 popular websites, including Booking.com, Aliexpress, and Teamviewer.

3. Attribution Fraud for app installs

Attribution fraud is also very similar to cookie stuffing, but focused on mobile app installs. In this case, fraudsters attempt to steal credit for app installs not generated by them. Attribution fraud tricks attribution platforms into associating an organic install or one created by another source with the fraudster, manipulating the “last-click attribution” model commonly used by attribution providers.

In early 2020, Google removed all apps from Chinese companies Cheetah Mobile and Kika Tech for practicing “click injection” and “click flooding”, two methods by which the relevant app attribution information was transmitted to ensure that the companies received the bounties for apps installed by users. The case made headlines as all of the developer’s apps were downloaded a total of over 2 billion times.

Another prominent case of attribution fraud occurred at Uber, where the company was defrauded of $70 million. Former Uber Head of Performance Marketing Kevin Frisch says:

“We basically saw no change in our number of rider app installs. What we found was that a number of installs we thought had come in through paid channels, suddenly came in through organic. I started gaining reports and I started seeing things that just did not make any sense. There is an app that has 1000 monthly active users and in theory we got 350,000 installs from them. We kept peeling this back, and we found that someone saw an ad and downloaded and opened the app within two seconds, which is just not possible. We discovered what we had was attribution fraud.” (Kevin Frisch @ Marketing Today Podcast)

An analysis by AppsFlyer found that 25.9% of app installs are fraudulent in some way, whether through fake installs or attribution fraud.

4. Typosquatting

Typosquatting means that affiliates register domains that are misspellings of advertiser domain names and immediately redirect users who accidentally land on them to the advertiser websites (Moore and Edelman, 2010). Here, the affiliate benefits from the fact that the advertiser has not protected these domains or excluded the use of such domains. Without its own advertising effort, the affiliate sets a cookie via the redirect and earns the commission.

5. Affiliate hopping

Affiliate hopping works only with advertisers who are part of more than one affiliate network. Fraudsters sign up with the affiliate program with each affiliate network and drop the cookies of all networks to receive commission for the same conversion multiple times.

6. Fake leads

In the case of fake leads, registrations that are compensated on a per-lead-basis are completed under invented or purchased registration data. Fraudsters also use bots in order to automatically fill out the forms.

The fraudster gets paid per sign-up and hopes that the advertiser checks the customer data too late or not at all.

7. Fake transactions

Fake transactions often involve the use of purchased illegal credit card data to generate a large number of transactions, for which the publisher then receives a commission. After all, the fake transactions are noticed afterwards, but the advertiser has often already transferred the commission to the fraudster at this point.

8. Brand bidding and ad hijacking

In brand bidding and ad hijacking, fraudsters pretend to be the owner of the brand or company whose name is being advertised. They copy existing ads on Google Ads of popular online shops and add their affiliate link to them. When users click on the ad, they are redirected to the online store where a cookie of the fraudster is placed.

In order to be listed before the original store, the fraudsters use a minimally higher CPC.

9. Email Spam

An affiliate link is included in emails sent out en masse. If recipients click on this link, they are marked with a cookie, which in turn, as with cookie stuffing, leads to the supposed affiliate receiving commissions for a service that it did not provide.

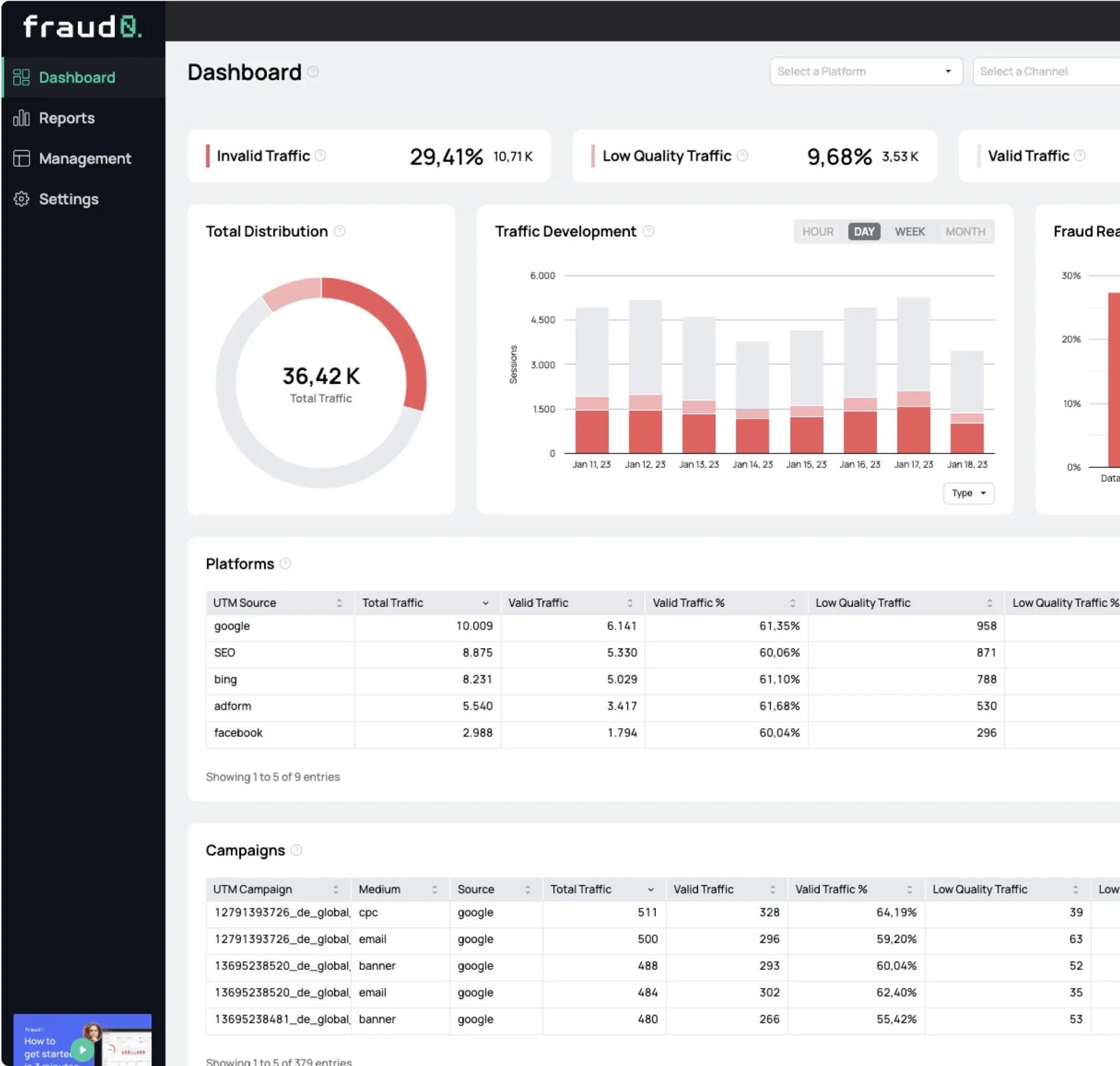

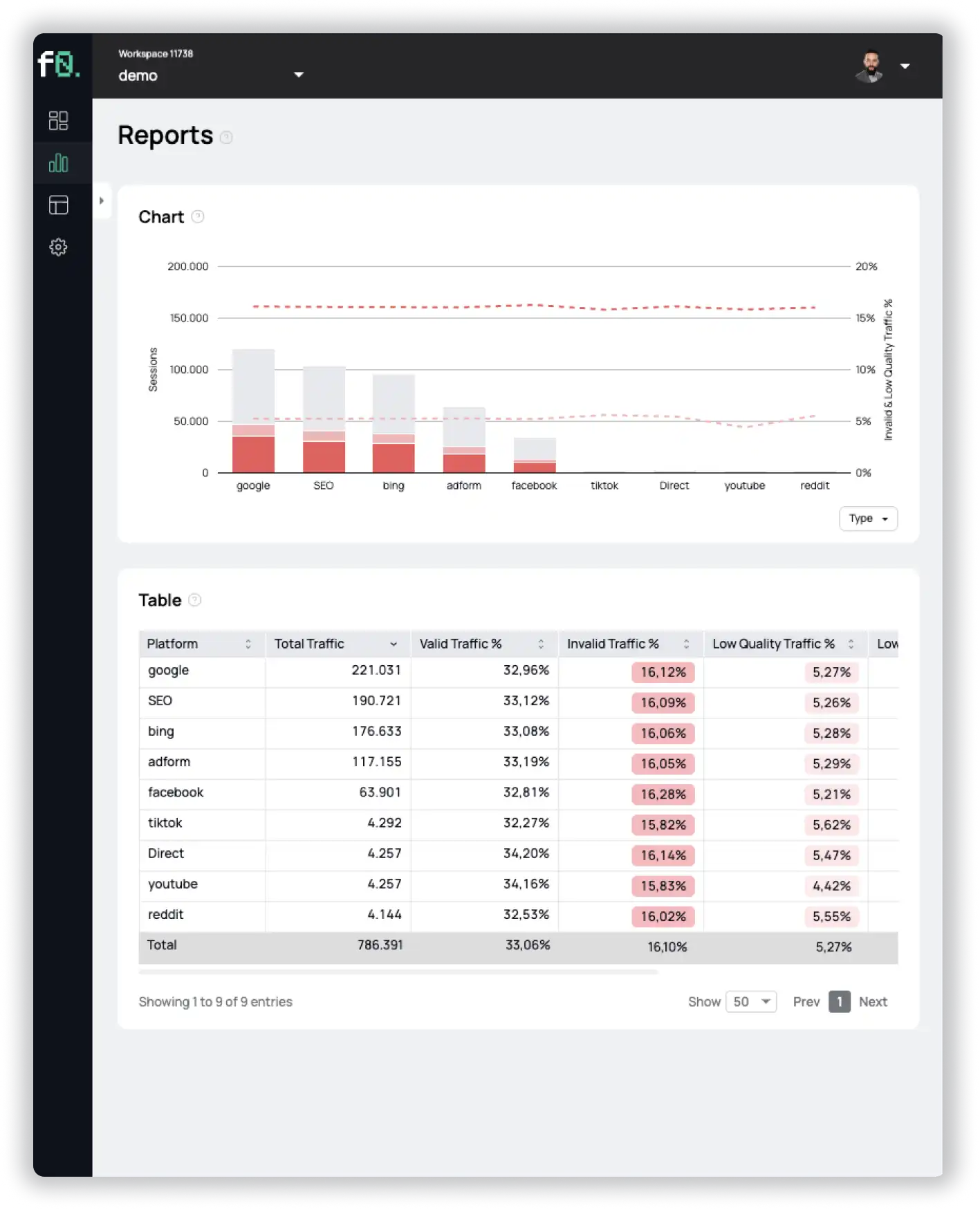

Indicators of affiliate marketing fraud

There are a number of indicators you should keep an eye on that suggest you are a victim of affiliate marketing fraud. Below, we will take a look at the most common signs.

1. Unexpected and sudden campaign improvements

As good as an unexpected increase in your campaign’s performance looks, you should be skeptical of the new numbers. Especially if you or your affiliate marketing partners have not made any significant changes to your campaigns like the introduction of new advertising materials.

If you notice a spike in leads during a lead generation campaign, immediately review the new contacts in your CRM. Also, if you notice an increase in new visitors from an affiliate, you should check your analytics tool for legitimate user activity.

Anomalies in campaign performance should always be monitored and investigated.

2. Low lifetime value (LTV)

Always check the lifetime value of your users and customers. If your product receives a lot of signups, but the in-product activity is very low or even zero, you might be a victim of affiliate fraud.

3. Traffic from unusual locations

Always review the traffic you are getting from your affiliates. If your business is based in Germany and you target mainly German users, sudden spikes in visitors outside this geographic region could indicate affiliate fraud.

Protect yourself from affiliate fraud

Affiliate marketing can provide many benefits for your business. But as with any other marketing channel, you have to be wary of fraudsters. The University of Illinois estimated that 38.1% of partners in the Amazon affiliate program engaged in fraud.

Define precise guidelines for your affiliate program, buy misspelled domain names yourself, prevent brand bidding and carefully vet each of your affiliates before approving them for commission payouts. Also, periodically review your reports and look for anomalies.

- Published: January 1, 2022

- Updated: July 2, 2025

1%, 4%, 36%?